HIIT that SIT!!

Oh, Thorny Roses, the day has come. We need to talk about HIIT, or even better, SIT.

Well, that is to say, I need to tell you about it, and it’s up to you to decide whether or not you want to do it!

Or, even more accurately, you need to decide whether you are going to do it, wanting doesn’t necessarily have to come into it!

In this article, we’ll delve into why this sort of movement is so beneficial for us, what the difference between the two is, why they are particularly useful for busy women, their benefits for the menopausal, and how best to do them, as well as what not to do.

If you’ve been regularly doing the daily exercises and incorporating some brisk walks into your week, you’ll be quite well primed for undertaking these more vigorous approaches. If not, now would be a good time to get more focussed on that! A certain amount of co-ordination and conditioning is required before going all-out on this type of exercise, but there are adapted versions you can do en route to true high intensity work.

What is HIIT and SIT? What is the difference between the two?

The acronyms themselves stand for High Intensity Interval Training, and Sprint Interval Training.

They have their origins in proper athletes getting proper fit, and that’s perhaps why it’s easy to think they don’t need to apply to us, who are perhaps just concerned with staying in reasonable shape and being able to run to catch the odd train, or keep up with any toddlers in our lives.

However, they are so beneficial that it’s really worth considering incorporating them.

What they are, essentially, is short bursts of intense exercise, followed by brief periods of rest or active recovery. In HIIT, the aim is to go for near maximal effort, for slightly longer, and in SIT, the intervals are at an even higher intensity, but for a shorter time, and the rest periods are a bit longer. SIT is really a subset of HIIT.

So for instance, HIIT might include 20 seconds of high intensity exercise, followed by 10 seconds of rest, and then repeated immediately for a number of rounds, which would make up one set. There would be a longer rest between sets, and you would work up to 3-4 sets. This could be in the form of speedy jumping jacks (if you’ve got the pelvic floor for that), fast-paced mountain climbers, or running on the spot.

SIT is all out, often with longer rest intervals than the work intervals. An example would running really fast (uphill is good if you are worried about tripping) or pedalling as hard as you can, for 8 seconds, with a 12 second rest. We’ll look at various options at the end of this article. It might be worth experimenting with a few to see what might work for you.

It’s also worth noting that you don’t do these very often. Potentially as little as twice a week every other week, or at the very most, a maximum of three times a week. Worthwhile benefits have even been recorded from just one session a week.

What are the benefits?

Ok, so, that’s what they are, but why should we do them? It has to be acknowledged, right from the start, that HIIT and SIT are, by their nature, hard work. Since you are always going for a percentage of your maximum output, getting fitter doesn’t make them easier - you just end up going harder. These are not the exercises you can do without warming up, without getting changed, or without showering (unless you have very tolerant co-workers). They are all about getting hot and sweaty and out of breath. But the pay-off is considerable:

Cardiovascular health improvements: both challenge the cardiovascular system by elevating the heart rate, leading to improvements in heart health including increased blood volume, improved blood flow, and lower resting heart rate.

Muscle Preservation: these workouts help preserve lean muscle mass, whilst promoting fat loss. This is good for maintaining metabolic rate and overall body composition. Wherever we are at with body positivity and not pandering to gender norms and such like, having a good muscle to fat ration has important implications for our long term health and longevity, as well as, more pressingly perhaps, what we can do now.

Metabolic Benefits: both types can enhance metabolic rate and improve insulin sensitivity, helping regulate blood sugar levels and reducing the risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes

Mental Health Benefits: the short intense bursts of activity in HIIT and Sit can be invigorating and energising, leading to improved mood and cognitive function, as well as reducing stress. Some studies have shown the effectiveness in treating depression to be as good as first line interventions such as cognitive behaviour therapy and anti-depressants.

Reduces Inflammation: HIIT and SIT trigger the anti-inflammatory response, leading to lower inflammation levels over time, which is a Very Good Thing.

Improves Immunity: when you start exercising hard, your “natural killer cells”, which fight infection, increase tenfold. Then, when you stop exercising, the levels in your bloodstream plummet, which might seem like a bad thing. Turns out, however, that these immune cells haven’t been destroyed - instead, they’ve been deployed to areas that are more likely to become infected - like your gut and lungs. Another Good Thing.

Enhances Cognitive Abilities: Do you remember that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)? Lifting weights stimulates it, and so does HIIT and SIT, improving cognition and working memory.

So, great benefits, but can’t we achieve the same going slower for longer? What’s wrong with steady-state cardio (aka, jogging)?

Well, we certainly do gain plenty of benefits from movement in general and exercise of various sorts - as mentioned in the Magic of Movement One and the Magic of Movement Two. But alas, when it comes to it, we can’t just go slower for longer and get the same benefits. In fact, there’s even reason to believe that doing a lot of steady state cardio can be counter-productive. This is sad news for me, because I am definitely more of a plodder than a sprinter.

It all comes back to that pesky cortisol. Long bouts of jogging (measured in hours rather than minutes) is perceived by the body as a stressor and that triggers the release of cortisol, particularly in older, menopausal women. One thing that the release of cortisol does is to break down lean muscle mass and add it to belly fat, for the oestrogen-producing qualities of active abdominal fat. It’s not that you’ve gone for such a long run that you’ve burned through all your fat stores and are eating into your muscle for fuel (probably), it’s that your body has preferentially sacrificed lean muscle mass because it thinks the belly fat will be more useful.

It’s also the case that this deep belly fat has about four times the number of cortisol receptors as regular subcutaneous fat, so deep belly fat triggers more cortisol production but it also leads to belly fat storage. It’s SIT you need to break this cycle. Societal standards of feminine beauty aside, visceral abdominal fat is not a good thing, and it is particularly hard to get rid of. It packs around our internal organs and increases the risk of high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes and some cancers. We really need this form of intense exercise to moderate it.

HIIT and SIT achieve this by encouraging your body to burn more fat for energy at rest, because it knows you will need the carbohydrates in your muscle and liver for the high intensity exercise that is coming. It also strengthens and increases the amount of your energy-producing mitochondria, which tend to become less functional over time. This means you will also feel more energetic the rest of the time. Lower intensity exercise doesn’t have this effect on the mitochondria, unfortunately!

It’s strange, because HIIT and SIT definitely feel stressful, but they don’t result in the same cortisol release as long steady state cardio, and in fact, they improve our response to stress. SIT seems to do this by pumping out more human growth hormone and testosterone and in so doing counteracts the cortisol, and reduces stress levels overall. HGH and testosterone are also anabolic (muscle making), and this also helps with improving the muscle-fat ratio of the body composition.

Does this mean you shouldn’t ever go for a long bike ride, or a long, slow, steady run? Not at all, of course, there are benefits to be had. Just make sure that you: fuel adequately (don’t do them as an attempt to create a calorie deficit); rest afterwards; and also incorporate HIIT and SIT within your week. Even if your goal is to become a distance runner, HIIT and SIT will help significantly with that.

For almost all of us, adding extra activity into our days via upping our step count, cycling instead of driving, dancing, gardening, doing daily OTHEH exercises, vacuuming vigorously, etc, will be a good thing. We don’t need to worry about cortisol doing those things. But running for longer than a couple of hours, especially if doing it in a fasted state (fine if you’re a man, less good if you’re a woman) or under-fuelled (again, actually beneficial for men), can be frustratingly counter-productive for our health and fitness.

Of course, it’s important to note that we all respond differently to exercise, as we all respond differently to food, and there are plenty of lean, toned, long-distance runners out there. But there are plenty of women who run a lot and find that as they go through the menopause their body composition is changing and that doing more actually makes it worse. Lean and toned might not be your ultimate aim, but if it is, HIIT and SIT can get you there in a way that steady state may not.

Examples of HIIT and SIT

The basic principle of HIIT and SIT is simple: you go all out, or nearly all out, for a short period of time, rest or do very light exercise for another short period of time, repeat a few times, for a relatively short but very effective workout.

There are, however, lots of variations.

You can vary the ratio between work and rest

You can vary the number of sets

You can vary the intensity of the workout

You can vary the frequency of the workouts.

I have to say, I’m particularly interested - as you might be, too - in the Minimum Effective Dose. What’s the least amount of this huffing and puffing I can do to elicit the beneficial effects in my body?

Oddly enough, there have been very few studies in this area, and I haven’t been able to find any that relate specifically to women, let alone older women. Plenty of studies demonstrate that HIIT and SIT have benefits that long steady exercise doesn’t, and I suppose it makes sense that when they made the comparisons, in the studies, they chose what they thought would be an effective dose, but didn’t risk using a regime that didn’t quite work.

But the consensus seems to be that a minimum effective dose might be twice a week every other week, as long as it really is high intensity.

If you’re not sure you’re really getting to that intensity high, every week would be safer. But three times a week is the absolute maximum that anyone suggests.

It’s also worth noting that because you don’t have to do it very often, you can still get considerable results from doing it from time to time; so if you fall off the high intensity exercise wagon, it’s always worth getting back on it, as long as it you are able to (so not suffering from injury, illness or fatigue). Or put another way, there are studies showing tangible results from just two weeks of HIIT or SIT training, of three short sessions per week. So, just 6 sessions can produce measurable results. Of course these would drop off over time, but if you even only just dipped into it from time to time, you would do yourself some good.

Let’s look at a few different ways of implementing HIIT and SIT. But before we do that, let’s remind ourselves of the difference and also how we can tell whether we are doing them at an adequate intensity.

Both of them rely on you working at a percentage of your maximum possible output, and we can gauge this in one of two ways: measuring your heart rate, or assessing the perceived exertion.

You aren’t going to measure your maximum heart rate, because this is really the top end of the scale that your heart can function at, so there are formulae to calculate what your maximum is likely to be. The simplest is 220 minus your age. So in my case, I’m nearly 55, so let’s use that, 220-55 is 165 is theoretically my maximum heart rate.

For HIIT to be effective, I would want to be working at 75% of this for that high intensity interval, so I would need to get to 124 beats per minute. If I were still in my twenties, say 25, 220-25 is 195, so I would need to get my heart rate up to 147 beats per minute.

For SIT, we are looking at an intensity of more like 85% of the theoretical maximum, so 55 year old me would be looking to hit 140 bpm.

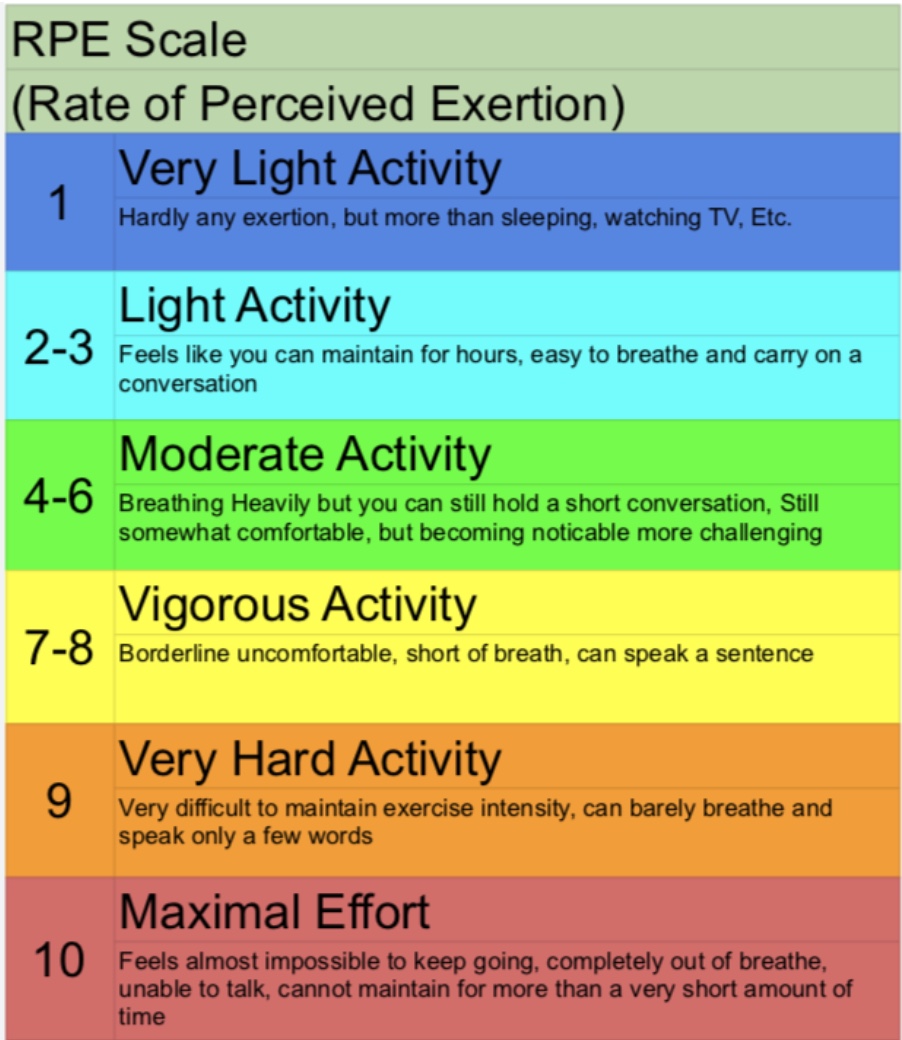

Obviously, you need something to be measuring your heart rate for this to work easily. Trying to take it manually would be quite difficult. If you don’t have an exercise watch (or indeed a proper heart rate monitor would be better, but most of us don’t have one just kicking about), you can go for a different approach, which is the Rate of Perceived Exertion.

This is simply a scale with “relaxed watching television” at one end and “being chased by a lion but honestly at this stage I think I’d prefer being mauled to death than continuing for a moment longer” at the other. It’s possible these are not the official designations. But you get the idea - you are looking for a high rate of perceived exertion.

The Official RPE scale

So with this in mind, let’s look at some of the ways you could do this.

DON’T FORGET TO WARM UP ADEQUATELY!!!!

At least 10-15 minutes warm up and a few minutes cooling down afterwards, too.

TABATA named after Dr Izumi Tabata, are one format you might use:

Go as hard as possible for twenty seconds, super easy for 10 seconds, repeat between 6 and 8 times. This is one set. Recover for 4-5 minutes with something super easy in between sets. Repeat the set. Work up to 3 sets. The thing you’re doing as hard as possible could be mountain climbers, running on the spot, kettle bell swings, cycling, running back and forth in a small space, anything you can do to get your pulse rate really up.

You can also double these up, to do 40 seconds on, 20 seconds off, which gives you a bit more time to settle in and push, especially if you don’t find it easy to get straight up to optimal intensity.

Hill Sprints

Charge up a hill as fast as you can for 20-30 seconds, walk back down to the start. Repeat 4-6 times. That’s one set. Rest 4-5 minutes between sets. Work up to 3 sets. If you have a long hill your warm up could be to take you nearly up to the top of the hill, then your resting in between sets is walking down the hill. Hills are much better than sprinting on the flat, which is harder on the body, and if you fall going up hill it’s not really such a big deal.

I mentioned earlier that, unlike our daily fare of easily incorporated into your life exercises, for these you really do need to warm up first. And because of the high intensity of the exercise, you do need to be quite well co-ordinated to do them at such speed. Sprinting for me, for instance, feels like it comes with some risk of tripping over if I were to do it fast enough for SIT, so I would rather run up a hill. If you were doing TABATA in the way that many do, of running backwards and forwards in a small space, it’s a lot of strain on the joints as you accelerate and decelerate. With kettle bell swings, you would need your legs and glutes to be particularly warmed up.

So one option is to simply start with a warm up that is specific to the type of HIIT or SIT you are going to be doing. So if you are going to be doing those TABATAs mentioned above, you start by jogging back and forth for a good ten minutes (or jogging over a bigger distance if you’ve got it handy), or do a variety of squats and lunges and then start with a few warm up rounds for the kettle bell swings.

Cycling is one of the easiest ways to do HIIT or SIT, either on a real bike or an exercise bike. On the rare occasions in the past that I’ve done SIT, this is the way I’ve found easiest, partly because I am out on the bike a fair bit as a mode of transport anyway. I’m not wanting to rush through a warm up because I’ve got several miles to cover in any case.

And this is worth emphasising: if you can incorporate this high intensity work into something that you already do, it can make it a lot easier to do. If you already go out jogging, add in some high intensity intervals into some of those jogs. If you already stride up hills, maybe try running up them for some of the walk. If you do a little boxercise, maybe do some high intensity striking in there.

One last and very important thing:

We mentioned that the maximum that anybody should do this is 3 times a week. It is also the case that you should *rest* following a truly high intensity workout. Not to say that you should take to the sofa for the next 48 hours, but definitely refrain from vigorous or extended exercise. The daily exercises we do, maybe less often than usual, would be fine. A mobility sequence would be great. A walk, a cycle on the flat (good luck around here), a swim, all of these would be considered active recovery, perfectly good, just don’t push yourself, and make sure that you listen to what feels right, and also, make sure you plan ahead!

The jury is out as to whether or not people with CFS or ME should undertake this sort of exercise. I found an article saying it had many benefits and no greater risk than moderate intensity exercise, and another saying that the first article had been largely discredited. Or at least, criticised. There are some extraordinary apps that can monitor your readiness for particular activities, how recovered you are from previous ones, and just generally how resilient you are likely to be. It might well be that that sort of monitoring and pacing is really helpful for those managing fatigue-related conditions.